Everyone remembers where they were when they heard the news.

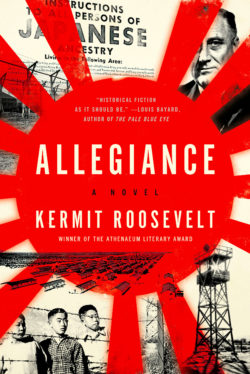

The following is an excerpt from Allegiance by Kermit Roosevelt.

The following is an excerpt from Allegiance by Kermit Roosevelt.

Everyone remembers where they were when they heard the news. I was in New York, the Beta house at Columbia, with constitutional law books on my desk and last night’s drinks in my head. Law school final exams fought with the debutante season for my attention. A doomed struggle; even without the pounding hangover, which pushed academic thought past bearing, Herbert Wechsler’s views on the Supreme Court could not stand against the white shoulders of Suzanne Skinner. They tanned honey-gold in the summer, with freckles like snowflakes of the sun. But as fall grew cold they paled to alabaster and in two weeks at the Assembly they would be white, as white as her dress, and you would barely see where the straps lay. And my hands by contrast would seem dark and rough as I steered her around the floor. And all about us the air would fill with . . . silence.

That wasn’t the right thought. The air would fill with waltzes and songs plucked from strings. But in the room now there was silence. It had stopped the clack of Ping-Pong balls from below and crept up the stairs; it had stilled the traffic on the street and slipped in through the window. Now it surrounded me, as though the whole world was a movie stuck between frames.

And then there were new noises. Outside, horns sounded and raised voices called, shrill and indistinct. Inside there was a clatter of shoe leather through the halls. Excited Beta brothers hurtled into the room. “Turn on the radio, Cash.” Exams and debutantes vanished; yes, and even Suzanne. The announcer’s words bred different images in my mind. Planes out of the blue Pacific sky, too fast, too low, too many. The sparkle of cannon fire from their wings, the smoke of ships afire at anchor, the red disc of the rising sun.

“The rats,” said one of the brothers, stubbing out a cigarette.

“Well, damn it, I’m joining up,” said another. Three of them rushed out, the echoes of their feet fading down the stairs.

For a blank second I sat there, watching the space where they’d been. Then everything came into focus in an instant, like putting on glasses for the first time, seeing suddenly all the sharp edges of the world, the crisp, clear lines of truth. “Wait for me!”

I dashed down the hall and took the steps four at a time, jumping off the top without thinking about where to land, launching myself again as soon as my feet touched down. We must have made quite a noise, but I heard nothing, saw only the boys ahead of me flying through the air. I burst out the front door onto the street. One of them—Jack Hamill, I remember the puzzled look on his face—was standing still on the sidewalk, head cocked as though an important thought had just occurred to him. The other two were rounding the corner onto 114th Street. I sprinted after them, threading through the pedestrians, darting past cars.

It took me only half a block to catch up. I was making good time, even in the crowd, and they were slowing down, turning their heads to exchange words, coming finally to a complete halt, faces as puzzled as Jack’s. I pulled up, panting slightly. “Why’d you stop?”

Pete Metcalfe turned to me. “Oh, Cash.” He sounded relieved and just a bit hopeful.

“What?”

“You don’t know where a recruiting station is, do you?”

“No.” I thought for a moment. “No, I don’t.”

Pete bit his lip. “Neither do we.” For a moment he looked as if he might cry.

We stood like sleepwalkers, woken in an unfamiliar place, impelled by a vanished dream. The urgency of the sprint was fading, the cloud of certainty, the single purpose. I could think of other things now, other people; I could imagine Suzanne’s reaction, and my mother’s. Running off without a thought for anyone else. I looked down at the sidewalk. By my feet lay a silver gum wrapper, a cockroach mashed flat. “I can’t do this.”

“No,” said Pete. “I guess not.”

Our walk back to the Beta house was slower. The radio was still on in my room, the brothers still clustered round. The ones who’d stayed barely looked up as we entered. Jack Hamill had taken my desk chair, and I found a space on the bed. And we sat there in silence, not meeting each other’s eyes, listening to the voices over the air and the metallic clanking of the radiators as the heat came on.

We sat there for hours, almost the rest of the day. But it wasn’t that long shared vigil that stuck with me in the weeks that followed. I never told Suzanne about how I’d run out; I never told my parents, or anyone else at home. The reaction came to seem absurd, almost shameful. So thoughtless, so irresponsible. But that was what I remembered in those later days, the feeling I had at the top of the stairs. Before we went down to the snarl of traffic and the realization we had no idea where we were running, there was the purity of that moment when I stepped out into space. When we soared above the jagged steps, our coattails flapping like ailerons, arms outspread to grasp the empty air.

Excerpt from Allegiance by Kermit Roosevelt, published August 25, 2015, by Regan Arts. ©Â 2016, Kermit Roosevelt.