Introduction

We are all Greeks. —Percy Bysshe Shelley, 1821

On March 25, 2014, Greeks marked the 193rd anniversary of the start of their war of independence against the Ottoman Empire.

On March 25, 2014, Greeks marked the 193rd anniversary of the start of their war of independence against the Ottoman Empire.

Young boys across the country dressed like klephts, the rebel highland bandits who fought the revolution, in white, pleated skirts called fustanellas, white stockings, red fezzes, and clogs topped with pom-poms. Girls wore traditional garb, tasseled headscarves and long colorful dresses embroidered with angular patterns distinctive to their region of Greece. In school auditoriums on the eve of the holiday, children performed plays about centuries of suffering under Ottoman rule. In a small valley town in the region of Messenia, the southwestern tip of the Peloponnese, a teenage boy dressed like a revolutionary bandit entered stage right and professed a yearning to fight for freedom: “What can I do? I can’t go on! My chest is heavy. The slavery of the Turk.” His mother, played by a girl in a yellow headscarf, urged him to stick to shepherding and to raising a family instead, but the young man was defiant. “Mother, bring the sword and the heavy rifle.” In a preschool on the Aegean island of Santorini, children young enough to still be wobbly on their feet tentatively circle-danced in front of their parents to “Dance of Zalongo,” a folk song about a mass suicide on a mountain in Greece’s rugged northwestern region of Epirus, where local women are said to have thrown their infants and themselves off a precipice rather than fall under the yoke of an Ottoman pasha. The preschool children in Santorini nearly fell over one another as the mournful song played over the speakers: “Farewell poor world, farewell sweet life, and you, my poor country, farewell forever.”

Such Independence Day rites are repeated annually with little variance, and though this was the first time I experienced the commemoration in Greece, I recognized a lot of these customs from my childhood on Long Island, where my Greek immigrant parents obligated me to attend Greek language and Sunday school classes at the local Greek Orthodox church. The church served as an outpost of cultural programming from the old country, and so the pom- pom shoes, the circle dances, and the indoctrination regarding Turkish tyranny were therefore already familiar to me. Still, this year in Greece, it was clear the usual rituals had taken on far greater significance. About four years earlier, Greece had begun hurtling toward bankruptcy, a situation that, owing to the nation’s eurozone membership, presented a potentially cata-strophic threat to the global financial system. In order to prevent immediate ruin, a trifecta of institutions known as “the Troika”— the European Commission, the International Monetary Fund, and the European Central Bank— agreed, despite deep reservations in Germany and other northern European countries, that it would be a good idea to sustain Greece, in particular its ability to keep servicing its vast debts, by pledging it tens of billions of euros in loans to be paid out in dribbles over a few years. The European leaders and IMF officials who committed the funds considered their intervention a “rescue,” though it didn’t seem that way to a lot of Greeks. The financial assistance was contingent upon wage and pension cuts, among many other profoundly unpopular conditions outlined in a memorandum of understanding— the mnimonio, as the Greeks called it. Control of the domestic policy was ceded almost entirely to the Troika, which used the threat of imminent bankruptcy as leverage to get Greece to obey its recipe for improving the country’s finances. But the recipe did not work out very well, and Greece’s economic collapse would begin to deepen to Great Depression—like levels, necessitating, less than two years after the first bailout, a second one. In total, Greece received 245 billion euros in loan pledges and the largest debt restructuring in history, which reduced its outstanding debt by 107 billion euros at the expense of private holders of its bonds. Moreover, the European Central Bank sustained damaged Greek banks with a constant flow of cheap short-term loans. In exchange for the bailout, Greek politicians promised profound changes to nearly every aspect of their governance, from the country’s deficient tax-collection practices to its regulations on the shelf life of pasteurized milk. The specificity of the required measures—the simplification of customs procedures for feta cheese exports, or the creation of a nationwide system of cadastral offices—underscored the Troika’s lack of faith that Greece could reform itself without strict oversight. In order to ensure compliance, Troika experts visited quarterly to check up on Greece’s progress. Failure to comply resulted in the withholding of scheduled payments. The Greeks, in short, would be forced to change under sustained duress. To a lot of Greek citizens, therefore, the rescue seemed more like a new foreign occupation. Independence Day seemed as good a time as any to reflect on this.

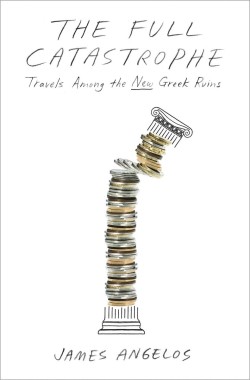

Excerpted from THE FULL CATASTROPHE: TRAVELS AMONG THE NEW GREEK RUINS Copyright © 2015 by James Angelos. Published by Crown, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC.